Dear Dick Couto,

I miss you—a lot. When you became the chair of my dissertation committee way back in 2009, I remember how excited I was. I was definitely a fangirl of your scholarship and your wry sense of humor. You made trouble. Good trouble. And in that, I found a kindred soul. It kicked up some drama when I stubbornly refused any other faculty member as my chair. I was trouble. Good trouble.

I think about you a lot lately. I now chair dissertation committees of my own, and I try to embody what you did for me. That’s a tall order, but it is the bar I attempt to meet.

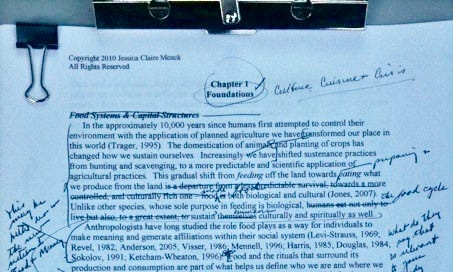

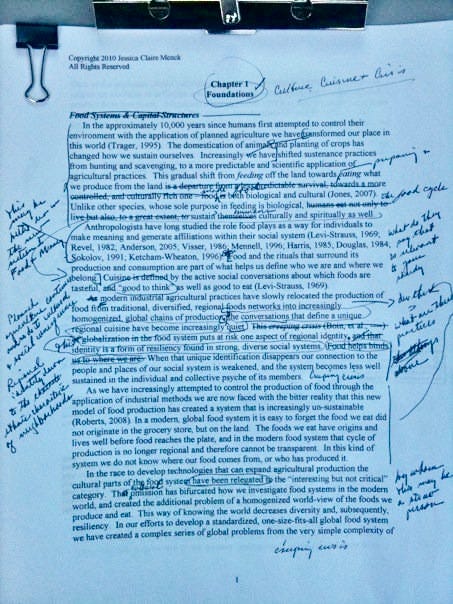

I realize I was an absolute handful as a student. When I started the doctoral program in Leadership and Change at Antioch University, I could barely write myself out of a wet paper bag. I had no idea what academic tone was or how to create it. What I did have were many big ideas that I couldn’t fit together in any logical sequence. I also had the stubbornness and tenacity of a mule. I genuinely believe this is why you are the only person who could have successfully guided me through my dissertation process. It was so painful and convoluted, yet you never wavered, even when I did.

Like when I had a looming deadline for the prospectus for my study. I was living in New Orleans then, a visiting scholar at Tulane University. I was itching to start fieldwork, but without the blessing of my committee, I was stuck spinning my wheels. I can clearly remember when you sent me an email and said something like, “This isn’t ready to go to your committee.” I was furious. I just sat on the mattress I was sleeping on the floor of my rat-infested studio in the Garden District and cried.

“Do I need to come to Virginia and work with you on this to get it done?” I emailed. I honestly thought you would relent with that threat, but you did not. “Yes, that would be the best way forward,” was all you responded.

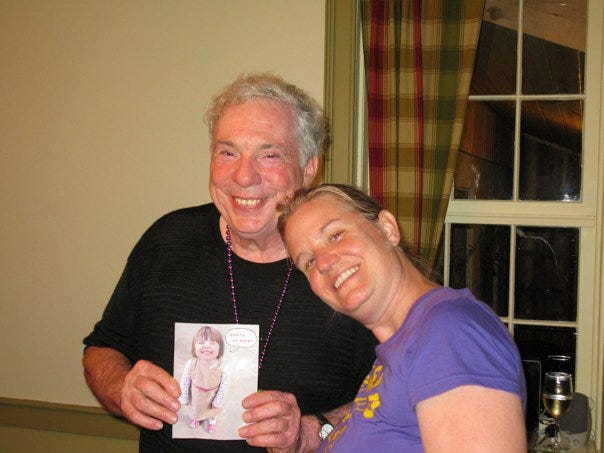

And so I went and camped (literally) in or about your front yard. I would get up in the morning and sit at your kitchen table with Took, your wife, and write. We’d have lunch and you would take two hours to read the draft and give it back to me. I sat and reworked it until supper time and left… to work on it more by myself. I did that for five grueling days. I’m not sure who that was harder on, me or you (or Took), but in the end, there was a draft!

The committee hearing was a train wreck, thanks in part to my insisting on having six committee members, not the standard four. Thankfully, my methodologist, Paul Stoller, was there to help me explain my method (ethnography) and why I did not have a hypothesis and variables to test. At that point, I was not able to do that myself. I won provisional approval by the thinnest hair of my chinny, chin, chin.

And then there was the fieldwork! A year in New Orleans when I took way too many risks in the field. God looks out for drunks and fools, so I guess s/he had my back there. I remember telling you things on the phone every week about my fieldwork, and you would sigh really loud, and there would be silence. I can only imagine what was going through your mind, but it usually resulted in a very slow and calm reminder about staying safe in the field. It must have been like talking to a teenager who just learned how to drive. Honestly, it’s kind of a miracle I came out of that year relatively unscathed. Although my car did get totaled the last week I was there.

Once I left the active fieldwork and started writing, it was like being lost at sea. I had no idea how to approach the boxes and boxes of artifacts and the hours and hours of recorded interviews. There was no AI to transcribe those interviews. There was no NVIVO, at least not the way it is today, to code all that data. It was all manual. So many notecards scattered everywhere. I remember when the wind would blow through my room; I would lose my mind trying to keep all those little bits organized in their piles instead of blowing every which way.

I think back on some of the things I wrote and sent you. I am one hundred percent sure they made no sense. They made no sense to me… but I had to spit them out of me and put them on the page so I could see the entire jumbled mess and then weave together a cloth from that.

And through all of that you told me to just keep writing. You would pepper me with questions I couldn’t answer because I thought they were the wrong questions, which meant I wasn’t explaining my findings correctly. Slowly, the light turned on. You weren’t being slow - I wasn’t being clear.

It was incredibly frustrating. I called you and quit about six times. I threatened to get a new chair at least twice. And each time, you just patiently listened to me explode and told me to keep going. Until one day, when you started on your insistent line of questioning, and instead of getting flustered and unable to answer, I responded with the data and how it connected to the theory. I just kept going, telling you why you were wrong about how I wrote myself into the data. I was there. I was a participant action researcher in the field, which made me part of the field. I was part of the data. I wrote in “purple prose” because that was the only way to express that particular data effectively. I kept going for a while. Until I stopped, you were just quiet.

“You’re ready to defend,” you said.

And I remember when I was driving to Yellow Springs, to my defense, you called me and told me to pull over. Fuck, I thought, what now? You read me comments from my committee’s read-through of the dissertation manuscript. The two people who had questioned the very rationale or need for the study both felt it was one of the most critical and profound investigations of how communities make meaning and build resilience after disaster that they had ever read. Except for some random edits, they all fully approved it.

So the defense was just a big party. Most of the people in my cohort were there. I broadcast the defense so people in New Orleans could live stream it (a first in 2012 when live streaming was not a thing yet). My best friend was there. We rented a house and had a huge party afterward. It was epic in every sense.

The dissertation went on to win several awards (you can read all about it HERE). That was nice, but what was better was that I now owned the skills needed to conduct ethnographic research and write about it. That last part has proven especially useful to me.

I can write. I can write fast. I can write logically. I can write effectively. But what I can also do is edit. I can sit with a paper (my own or someone else’s), read it sentence by sentence, and wordsmith the hell out of it. I can see the narrative arc in a piece of writing or where that arc is missing. It’s incredibly gratifying to be able to do this. It’s like having a superpower.

Occasionally, I will sit with students and do this with their papers like you did with mine. The response is always the same - wide-mouthed awe. The light goes on when they watch me do this. Every time I have done this with a student, it has dramatically shifted how they write and edit.

Which brings me back to today. I now have students of my own. Each one of them is so different. I am blown away by their topics and how they build their studies. Each of them is just such a gift to this world and academic scholarship. They are carrying on the good fight. They care deeply about the problems they see, and they want to understand why the world is how it is. You would just love the things they are studying. There is such a direct line from you to them, through me.

But each one of them also struggles. They get frustrated. Sometimes, they blow up at me. Usually, after I say, “Just keep writing; you’re not there yet.” More often, though, we have the same kinds of conversations you and I had. We plumb the depths of their ideas and their scholarship. It’s immensely gratifying for me, like I now realize it was for you. I know it would make you happy to know that the legacy you bequeathed me is now going on to the next generation.

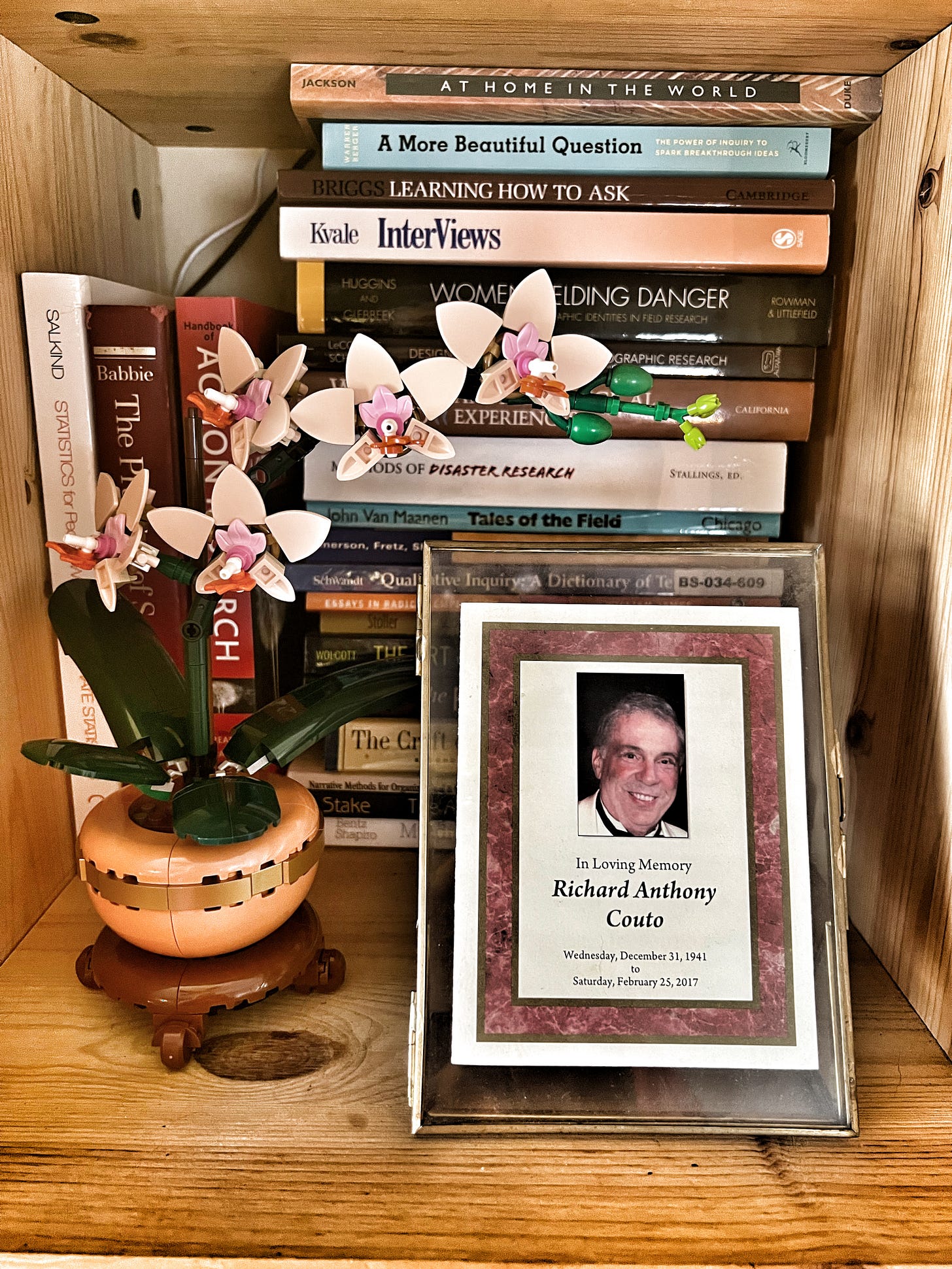

I have a picture of you sitting on the shelf behind me in my office. Now, I meet with students on Zoom, and I often point to you and tell them stories about when I was a doctoral student. And I often think that you are probably somewhere looking down, especially when I have a student who is so frustrated with me, and every time I do that, it makes me tear up because I now understand how hard it must have been for you to know how furious I was with you, and yet, you held the line. You never accepted less than what the academic standard of excellence demanded. You had a clear understanding of what good scholarship was and would not let me produce anything but that level of work.

I think part of that was because you knew what would happen when the work went into the world. I had to defend it to you and my committee because the world would be even more relentless in tearing it apart. You taught me how to defend myself, the people and ideas I studied, and the data with my words.

That’s the thing about being a mentor, parent, or teacher…. your significant function is to “hold the space,” as Ronald Heifetz would say (you introduced him to me!). It’s our job to make a container where a student can spit up the work and beat it up until it makes sense, and they can fight for it. There’s a reason the last hurdle to a doctoral degree is called a “defense.”

Students have to wander in the dark. The teacher’s job is to hold the map and the flashlight, but in the end, we have to let the students walk the path by themselves. We can be right there, tight at the start, but as we go further down the road, they eventually take the map and the flashlight and go on without you. They don’t need you anymore because they know how to do it themselves.

I guess I’m over here walking my own path now. But I have to tell you, I wish you were here to talk about some of this stuff. I still struggle so much with my own fieldwork… I’m two years into the current project I’m working on, and it’s completely off the rails. I just want to throw it away and start something completely different. I wish I could talk to you about that. I wish I could hear that sigh and long silence again, followed by the always sage, “Just keep going; you aren’t there yet.”

Thanks to you, I got there once, Dick, and I’ll do it again.

Yours in the struggle,

Claire